Ten Commandments for Leading Change

Change leadership is an extremely important topic for every organization that wishes to survive. Our consultant Vesa Hack introduces his 10 commandments for leading change.

Change leadership is an extremely important topic for every organization that wishes to survive (or even better, to prosper) in the constantly changing environment. According to researchers Aquirre, Alpern and von Post (2013), the success rate of major change initiatives is low, only 54 percent. They have recognized three reasons that cause the low success rate of change programs:

- “Change fatigue”: people feel exhausted and pressured when too many transitions are being made at once.

- Lack of skills to ensure that change is sustained over time: leaders should invest in operational improvements, instill new practical approaches and give people the knowledge and cultural support they need.

- “Top-down” practices in change implementation: transformation efforts may be decided upon, planned, and implemented by the top management. Without input from those at lower levels, useful information is left out and frontline ownership of the change might be limited.

As a business consultant and service designer, I constantly experience the change around me in different customer organizations. In my experience, the above mentioned three issues could be used to characterize majority of change initiatives. Based on these issues, and theories about business change leadership, I formed my own instructions for leading change.

1. Accept that change takes place in tangled webs of relationships

Many organizational change programs have been planned and led as systematic processes with incremental steps, just like a development process for a machine. But human organizations are filled with living beings, and change occurs in the tangled webs of relationships.

Most communication and change occur quickly but invisibly, concealed by the density of interrelationships. If a living system chooses to be disturbed, it takes in the information and circulates it rapidly through its networks. The information may swell to such importance that the system can't deal with it in its present state. Then and only then will the system begin to change.

This is why "top-down" managed, incremental change projects often fail. The people in the organization might not have yet chosen to be disturbed about the present state. Of course, it is possible to effect on the people in the organization, but it is important to admit that the nature of change makes it impossible for the management team simply command the organization to change.

2. Understand and value the psychological contract

In addition to their official contract, people have a psychological contract with their organization. This includes their perceptions of the employment relationship and expectations for oneself and the organizations as well as perceived norms, rights, rewards and obligations.

Much of the psychological contract is implicit and change leaders are often unaware of its importance. It can be changed, but engagement is essential. Sudden and arbitrary changes can cause resistance and lead to failure.

3. Understand the reasons why people resist change

There are four basic reasons why people resist change: they do not want to lose something of value, there is a misunderstanding of the change and its implications, there is a belief that the change does not make sense for the organization, and there is a low tolerance for change.

Overcoming resistance requires understanding the root cause of it. The underlying causes should be found out.

4. Analyze the key situational factors when choosing the change strategy

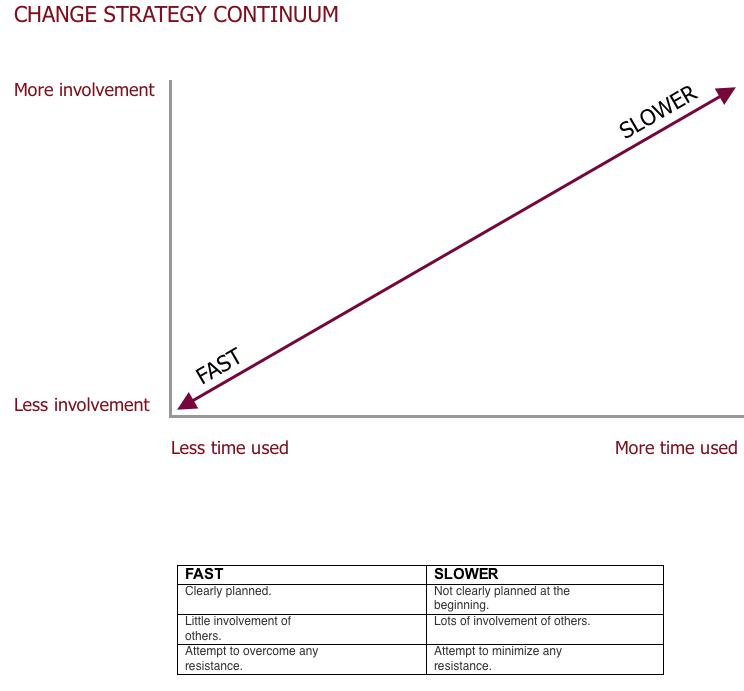

The strategic options available to managers can be thought of as existing on a continuum. At one end of the continuum, the change strategy calls for a very rapid implementation, a clear plan of action, and little involvement of others. At the other end of the continuum, the strategy would call for a much slower change process, a less clear plan, and involvement on the part of many people other than the change initiators. The further to the left one operates on the continuum, the more one tends to be coercive and the less one tends to use the other approaches.

Before deciding on the change strategy, one should analyze the key situational factors that affect on the success of the change.

Key situational factors for the choice of strategy are:

- The amount and kind of resistance that is anticipated. The greater the anticipated resistance, the more difficult it will be simply to overwhelm it, and the more a manager will need to move toward the right on the continuum to find ways to reduce some of it.

- The position of the initiator vis-àvis the resisters, especially with regard to power. The less power the initiator has with respect to others, the more the initiating manager must move to the right on the continuum. Conversely, the stronger the initiator's position, the more he or she can move to the left.

- The person who has the relevant data for designing the change and the energy for implementing it. The more the initiators anticipate that they will need information and commitment from others to help design and implement the change, the more they must move to the right.

- The stakes involved. The greater the short-run potential for risks to organizational performance and survival if the present situation is not changed, the more one must move to the left.

5. Lead with culture

Instead of trying to change the company culture itself, change leaders should draw emotional energy from it. The cultural elements that are aligned to the change should be brought to the foreground in order to create change ownership by the people who will be affected by the change.

Culture should be known and recognized, and all change communication should be planned so that it resonates positively with the existing culture.

6. Empower the people

In their article, Wheatley and Kellner-Rogers (1998) state that people genuinely support the change when they feel that they have created it themselves. People should be invited into the process of rethinking, redesigning, restructuring the organization. When people are involved, they will create a future that already has them in it.

It is important to recognize the individuals with informal authority as well as those with formal authority. According to Aguirre and Alpern (2014), change has the best chance of cascading through an organization when everyone with authority and influence is involved: those who hold formal positions of power, as well as people whose power is more informal. Informal power might be related to people’s expertise, breadth of their network, or to personal qualities.

7. "Walk the talk"

Successful change management initiatives start at the top, with a committed and well-aligned group of executives strongly supported by the CEO. This group should agree about the case for the change and the particulars for implementing it.

People will not begin to shift their behaviors once formal elements like directives, incentives and organizational charts have been put in place. It is critical to ensure that people’s daily behaviors reflect the imperative of change. Senior leaders must “walk the talk”, right from the start, and then employees will believe that the change is real. If the top management doesn’t agree about the change or their support is not genuine, people will become confused.

8. Support the internal change in each of us

In order to achieve collective behavioral change over time, activities that support the individual personal change of each and every one of us are needed. Companies that only look outward marginalize individual learning and adaptation. Those who seek to lead powerfully and effectively need to look at their internal experiences, precisely because they direct how we take action, whether we know it or not.

Boaz and Fox (2014) represent two dimensions of looking inward: developing profile awareness and developing state awareness.

1. Profile awareness

An individual’s profile is a combination of habits of thought, emotions, hopes, and behavior in various circumstances. Profile awareness is a recognition of these common tendencies and the impact they have on others.

2. State awareness

State awareness is the recognition of what’s driving oneself at the moment of action. State awareness involves the real-time perception of a wide range of inner experiences and their impact on one’s own behavior. These include the current mind-set and beliefs, fears and hopes, desires and defenses, and impulses to take action.

Organizational change is not inseparable from individual change. People change, organizations do not. Therefore, change leaders should develop their own internal awareness and also support others to do the same.

9. Recognize the importance of communication

Entering into a world of shared significance is only achieved by engaging in conversations with colleagues. We don't have to agree on an interpretation or hold identical values in order to agree on what needs to be done. We don't have to settle for the lowest common denominator, or waste hours and hours politicking for our own, decided-on-ahead-of-time solution. As we sit together and listen to so many differing perspectives, we get off our soapboxes and open to new ways of thinking. We have allowed these new perspectives to disturb us and we've changed.

10. Demand and ensure that the change actually takes place

In order to lead the change successfully, it is important to engage, empower the people, take psychological contracts into consideration, and apply many other people-centric leadership methods. But while all this is being done, it is at least as important to demand and ensure that the change actually takes place.

According to Schaffer (2010), there are four behavioral traps that thwart organizational change.

1. Failing to set proper expectations

Leaders announce shifts in goals or direction without spelling out specifics, saying who's accountable, or setting clear deadlines.

2. Excusing subordinates from the pursuit of overall goals.

Managers allow employees to focus narrowly on their units, and so responsibility for company wide performance gets "delegated" upward.

3. Colluding with staff experts and consultants.

Executives permit experts to deliver solutions without assuming responsibility for outcomes.

4. Waiting while associates prepare, prepare, prepare.

Endless preparation gives the illusion of progress but ultimately gets in the way.

In a nutshell, successful change leadership seems to be extremely dependent on the collaboration and communication in the networks. In order to be successful, the change should be co-created in the network and a lot of attention should be put on provoking communication among people.

Change is all about the people who make it and feel ownership about it.

Sources:

Aguirre, D.A. & Alpern, M. 10 Principles of Leading Change Management. Strategy + Business, Summer 2014. Issue 75. https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00255?gko=9d35b

Aguirre, D.A., & Alpern, M. & von Post, R. Culture’s role in enabling organizational change. Strategy&. Originally published by Booz & Company: November 14, 2013. https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/reports/cultures-role-organizational-change

Boaz, N. & Fox, E. A. Change leader, change thyself. McKinsey Quarterly, March 2014. McKinsey&Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/change-leader-change-thyself

Schaffer, Robert H. 2010. Four mistakes that leaders keep making. Harvard Business Review. 2010. September, Vol. 88 Issue 9, p86-91.

Wheatley, M.J. & Kellner-Rogers, M. 1998. Bringing Life to Organizational Change. Journal for Strategic Performance Measurement, April/May 1998. https://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/life.html

Tilaa blogikirjoitukset sähköpostiisi